http://www.washingtoncitypaper.com/display.php?id=561&navCenterTopImg

The Missing Link

We like to think the half-smoke is D.C.'s indigenous street food. So why don't we know anything about it?

The first half-smoke I ever tried came off a downtown D.C. vendor cart at the corner of 5th and F Streets NW. I was relatively new to Washington at the time, and yet I’d already heard that this sausage was exclusively a D.C. thing. I’d even gathered from a few recent D.C. transplants that I’d never make it as a local until I’d sampled a few half-smokes. Eating processed meat struck me as a particularly lame path to D.C. cred. But it cost only $2.25, chips and soda included.

What the vendor passed me was a plump, gelatinous frank with a circumference nearly twice that of a typical hot dog. On the vendor’s recommendation, I had it smothered in mustard and diced onions. At first bite it seemed to taste no different from your everyday dirty-water dog, but as I worked my way down the frank, I was hit with more and more spice. In the emulsified beef I could see the tiny culprits: Flakes of what I figured was red pepper.

Since then I’ve eaten more half-smokes than I can count—off carts, at local greasy spoons, out of butcher shops—and yet I don’t think I’ve ever been served a half-smoke identical to that first one. In fact, many of the half-smokes I’ve eaten barely resembled one another. And the more vendors and half-smoke lovers I chatted up, the more D.C. grillmen whose ears I bent, and the more regional meatpackers I called, the further I got from a firm definition of the half-smoke.

Depending on whom you ask, the half-smoke is simply a smoked sausage. Or it’s a sausage that’s been smoked only halfway—whatever that could possibly mean. Or maybe it’s a half-smoke because some cooks prefer to split it in half when it goes on the grill. Or its “half” comes from the fact that it’s often made from equal portions of beef and pork. But then how do you explain all those half-smokes downtown that are advertised as all-beef?

And if the half-smoke means nothing to anyone outside D.C., why can I buy a box of “Ragin’ Cajun style” half-smokes at the local meat shop?

Most local foodies who happen to be lifelong Washingtonians can agree on one thing: The half-smoke is D.C.’s signature street food and arguably its only indigenous dish.

But what the hell is a half-smoke, and how did it get here?

(Photograph by Darrow Montgomery)

(Photograph by Darrow Montgomery) Ever since the hot dog emerged in American cities, countless politicians have demonstrated their worthiness to voters by making a spectacle of their sausage consumption. Smoked links have served as cheap sustenance for the common people as far back as ancient Greece, where Homer wrote of blood sausage roasting over a fire, so the thinking goes that wolfing down a few dogs might mean something to Joe Citizens at the ballot box. As New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller reportedly quipped while on the hustings in 1969, “No man can hope to get elected in New York state without being photographed eating hot dogs at Nathan’s Famous.” The same can be said for Washington D.C.’s Ben’s Chili Bowl.

No politician has used chili dogs and half-smokes as shortcuts to D.C. accreditation quite like former Mayor Anthony A. Williams. Long accused of being aloof, overly academic, and insufficiently black, Williams compensated for his lack of common touch by associating himself with Ben’s Chili Bowl at every possible turn. He mentioned the place in his inaugural address, and he made it his first stop after he won office in 1998, according to the Washington Post. In a January 2005 Q-and-A with the Post, Williams cited Ben’s as the “restaurant where my constituents would most likely run into me.” And when he was spotted eating a turkey chili dog there in the summer of the same year, some observers took it as a sign that he might actually seek a third term.

How did Ben’s and the half-smoke become such icons of Washington culture? “As I think about it, I often wonder if Bill Cosby didn’t play a major role,” says Virginia Ali, who co-owns the Chili Bowl with her husband Ben. The story goes that Cosby first came across the half-smoke when he was in the Navy and stationed at Quantico in the 1960s.

(Photograph by Darrow Montgomery)

(Photograph by Darrow Montgomery)

When he came to town in 1985 to promote the premiere episode of his soon-to-be-watershed sitcom The Cosby Show, he spent some time at the Chili Bowl being mobbed by fans and telling a reporter how he used to take a young Camille Hanks there on dates. Subsequent press reports about Ben’s often noted how Cosby could devour three of the sausages in a single session. And when Cosby went on The Oprah Winfrey Show, the talk-show host surprised him with a batch of Ben’s half-smokes she’d had brought in for the taping, allowing Cosby to bring a small piece of Washingtoniana into the homes of millions of Americans.

In 2000, the Washington Post Magazine queried readers in a contest to determine Washington’s “signature dish.” The undisputed winner: the half-smoke.

Tom Carey can testify that the half-smoke is indeed a geographically defined food. He’s an account manager with Esskay Inc., the Towson, Md.-based distributor of one of the District’s bestselling half-smokes. “It’s a D.C. item,” insists Carey. “Twenty-four miles down the road they don’t know what they are.” Carey believes the name comes from the fact that a half-smoke has “half the seasoning” of a Polish sausage—in other words, it’s halfway to being somebody else’s sausage. “That’s what I was told, anyway,” says Carey. “But that and 50 cents will get you a cup of coffee. I wouldn’t put much [stock] in it.”

If anyone knows how the half-smoke took root on our streets, there’s an outside chance he would have once worked at Weenie Beenie, that resilient grill opened in 1954 in the Shirlington section of Arlington by one-pocket billiards champion and trick-shot legend Bill Staton, four years before Ben Ali opened his now-famous Chili Bowl in the District. Weenie Beenie remains one of just a few local eateries that have been grilling the item since an apparent half-smoke heyday in the 1950s.

The grillmen at Weenie Beenie serve the half-smoke the same way they did back then: split down the middle so that it’s hinged, grilled face-down and then flopped onto its back, and dressed with house-made chili sauce, mustard, onions, and relish—“all the way,” as the cooks call it. (The owners subscribe to the theory that the name “half-smoke” derives from its being cooked in this split fashion.) And they still serve their unique breakfast-style half-smoke sandwich conceived decades ago: a split sausage laid atop a fried egg and blanketed with American cheese—a cheap, relentless attack of sodium and protein that does a fine job of sustaining the day laborers who wait for work each day in a nearby parking lot and who account for much of Weenie Beenie’s business nowadays.

“The newer generation, they’ll call it a kielbasa,” says manager Travis Hackney. “Or they’ll ask for the ‘bigger hot dog.’ But the older guys know what it is.”

Travis’ father, owner Theo Hackney, has been at the helm of Weenie Beenie since November 1956, when he used to roll out of bed before dawn to put more than 40 pounds of half-smokes on the grill to prepare for the morning onslaught of working-class customers. (The 76-year-old Theo still arrives at one of Weenie Beenie’s sister grills, Burger Delite in Alexandria, at 4:45 to get a jump on the half-smokes and other breakfast fare.) When asked about the different kinds of half-smokes available back in the day, Theo says there was just one—“the original”—and that it was the best Washington would ever see.

By “original,” he means the sausage that was distributed by D.C.’s own Briggs and Co. meatpackers. These popular links were grilled in the small, aluminum food shacks that dotted the roads throughout the Washington area at mid-century—places much like Weenie Beenie, most of which have long since died off. Back then, says Theo, the half-smoke was as ubiquitous as it was flavorful.

“Those little kitchens were sitting all around town, and they sold three items: half-smokes, hot dogs, and hamburgers. Very few of them even had French fryers in them,” recalls Theo. “The original half-smoke was extremely good.”

Virginia Ali confirms that the Briggs half-smoke was the half-smoke she and Ben knew when they opened their doors in 1958. A sign heralding Briggs hot dogs and half-smokes hung in their window.

This “original” half-smoke was no emulsified dirty-water dog. It was a high-quality sausage made up of coarsely ground pork and beef—the kind of heterogeneous texture that assured you your frank came from actual animals rather than a technologically enhanced paste. Augmented with precious few additives, it came smoked and enclosed in a natural casing that snapped on the first bite. It was meant to be grilled.

(Photograph by Darrow Montgomery)

(Photograph by Darrow Montgomery) In the years following World War II, the Briggs meatpacking company distributed its half-smokes to markets and grocery stores throughout the city from its plant on 11th Street SW, in what was then the city’s robust meatpacking district. Among the family butcher shops and greasy spoons from that era that survive today, it is generally assumed that the half-smoke was born sometime decades ago in that long-demolished Briggs plant.

Owner and co-founder Raymond Briggs, a lifelong Washingtonian who was born on Capitol Hill in 1896, was the son of a butcher. His father, Frederick, ran a meat stand at the northwest corner of the old Center Market, at Pennsylvania Avenue and 7th Street NW, which at the turn of the century was D.C.’s largest market, covering two square blocks in the city’s business district and providing space for some 700 merchants. It was there as a child that Raymond learned the meat business from his father, helping unload the smoked sausages and hams that were transported by horse and buggy.

When Raymond came of age, he launched a meatpacking company with two of his brothers. Briggs and Co. grew into one of the largest packers of its kind in the mid-Atlantic, and the Briggs name was eventually recognized by any homemaker who shopped at Safeway or any Senators fan who ate a dog at the old Griffith Stadium. At some point, probably in the 1930s—exactly when is hard to pin down—Briggs began selling its half-smoke sausage.

There is no definitive half-smoke creation story. Ask a street vendor where this locally renowned sausage sprang from, and you’ll be greeted with a blank stare, then informed that you’re holding up the line. Ask an old-guard butcher at one of the city’s meat-and-produce markets, and you might be lucky enough to hear a story, but whatever the butcher knows about the District’s meatpacking history likely came from his old man—or his old man’s old man—and any such story will usually come with the disclaimer that it can’t be trusted.

But 69-year-old Jack Dekelbaum has some reliable memories of the Briggs empire. His family meat shop, Leo Dekelbaum & Sons, which opened in 1935, still sells half-smokes at its location in the Florida Avenue market in Northeast D.C. (Due to health reasons, the Dekelbaums will be selling their shop at the end of this month after seven decades in business.) Dekelbaum recalls having to run to the Briggs plant to pick up hams and hot dogs for his father and uncle as far back as the late 1940s. “Once you hit the Southwest side coming from Southeast, you could just smell the meat smoking,” he says of the Briggs plant.

When he was a kid, Dekelbaum says, legend had it that the Briggs folks had concocted the original half-smoke in a kitchen laboratory at the plant, where they devotedly searched for that unique interplay between protein, fat, spice, and smoke.

“It was a secret recipe they formulated themselves,” Dekelbaum says. “They were the first and the biggest sellers of half-smokes and hot dogs for many, many years. Briggs had [what they called] ‘the famous half-smoke for the City of Washington.’ They had one which was skinless and one which was skin-on, more in the European style. It was generally pork, beef, and all types of spices. Hot and mild.” As an observant Jew, Dekelbaum never learned of the quality of a Briggs half-smoke by way of his palate—he just knows they were one of his father’s most popular items. “Fifty-four to a box—I still remember the count,” he says. “We sold more half-smokes than anyone else in the city….Briggs was just one of the best local brands.”

And what a name to bestow on a sausage: half-smoke. The curt, mysterious phrase seems as if it were designed to be barked inside busy city grills.

Although we may never know who was in the kitchen when that first half-smoke sizzled on the grill, it’s likely that Raymond Briggs himself had a hand in the original recipe. Briggs died in his home on Connecticut Avenue NW in 1988, but his two surviving daughters remember him not as a distant, uninvolved CEO type but as a devoted butcher.

“My father used to bring [sausages and hams] home every night, and he was always trying to perfect them,” recalls Briggs’ 80-year-old daughter, Mary Jayne Winograd. The Briggs children served as taste testers. “We were kind of guinea pigs,” explains his other daughter, Margaret Delp, also 80.

Both Winograd and Delp say their childhoods were filled with half-smokes and hams. Their mother used to cook the sausages as part of the lavish family breakfast they had every Sunday. The half-smoke was pretty much a morning thing back then, and the Briggs family ate theirs alongside hotcakes.

Even given Raymond’s gustatorial enthusiasm, the Briggs children don’t know for certain that their father was the man who gave D.C. a sausage link of its own. “I have no idea as to how it was developed,” laughs Winograd, a little surprised that anyone might care. “I’m not really sure who was behind it—maybe it was my father, maybe it was his father, Frederick.”

Says Delp: “I would think it was my father, but I don’t know that for sure.”

(Some people erroneously assume the half-smoke was created by Raymond’s brother Albert, who founded AM Briggs, a meat and poultry distributor that had no relation to the sausage company but still survives on Queens Chapel Road in Northeast D.C. The two companies still get confused. “It’s kind of funny,” a worker at AM Briggs told me over the phone. “Here we are selling thousands and thousands of pounds of meat [to hotels], but we’ll always have some guy who walks in here looking for a few half-smokes.”)

Whether he created the half-smoke or not, Raymond Briggs, by all accounts, was proud of his company’s signature sausage. When D.C. native and renowned local foodie Joe Heflin was driving a cab while in college during the late ’60s, he once gave the sausage maker a ride to his home in Bethesda, Md. After the two enjoyed a pleasant conversation, Heflin recalls, Briggs ran inside and came out with Heflin’s tip—a package of half-smokes. “And at the time that was a good tip,” says Heflin. “The pack of half-smokes was worth more [money] than most people gave.”

Eastern Market butcher Bill Glasgow Jr., whose father launched the Union Meat Company in D.C. in 1946, remembers the name Briggs and the term half-smoke being so linked in the meat business that he believes the company had exclusive rights to the sausage name. “It was like Kleenex,” says Glasgow. “ ‘Half-smoke’ was their name, and Briggs’ was the definitive half-smoke….You couldn’t say you had your own.”

But Briggs and Co. eventually grew too profitable for the half-smoke’s good. When the time was right, Raymond Briggs sold the outfit to another meat distributor. A stickler for quality, Raymond stayed on as a consultant with the new company for two or three years until he was essentially told to beat it. According to Winograd, the new conglomerate “literally destroyed the product, wanting to make it cheaper.”

The Briggs half-smoke lives on today, though in name only to most minds; the thick, gelatinous frank sold under the Briggs banner more closely resembles an oversize hot dog than the bratlike sausage of yesteryear.

It’s a shame that the spicy frank found on downtown carts has become so widely considered the definitive half-smoke. Far from being handmade sausages, these smoked, casing-less links are created in an industrial process known as emulsification, whereby water and lower-grade pork or beef cuts are fused into what meatpackers refer rather disturbingly to as “batter.” It all makes for a satisfying and exceptionally cheap quick bite, but it’s not the half-smoke to which out-of-towners should be introduced.

A close approximation to the original half-smoke can still be found at Weenie Beenie, where the mild sausage “is as good as we think we can get,” says Theo Hackney. “It still doesn’t hold up to the old Briggs half-smoke, but it does a fairly good job.”

As for Ben’s, there are some local grease connoisseurs who feel the Chili Bowl’s stature as a cultural landmark of black Washington long ago outgrew the quality of its grub. These foodies would never publicly trample on a piece of D.C. history like Ben’s, but in trusted company they’ll recite the same litany of complaints: Ben’s chili can be too runny; the fries lack crispness; and the chili burger falls short of the restaurant’s renown.

But Ben’s half-smoke remains unimpeachable. It doesn’t come cheap—$4.55 on its own, with or without chili, which is costlier than even the hamburger—but when it comes to sausage, you get what you pay for. Ben’s version has everything a good half-smoke requires: the snap that comes with a bite, courtesy of a natural hog casing (“that pop,” as Virginia Ali likes to say); the coarsely ground pork and beef insides, bound just tightly enough to hang together but not so tightly as to make the link stiff; and, finally, just enough kick to remind you where you are and exactly what you’re eating.

“In the very few times there’s been a manufacturing issue, we’ve had a hell of a time finding a replacement,” says 37-year-old Nizam Ali, Ben and Virginia’s youngest son, who now runs the Bowl with his brother Kamal. In a pinch, the Alis once tried to sub the regular half-smoke with kielbasa. Patrons took notice. “If [the packing plant] is down for 24 hours, you’ll find a replacement and people won’t like them. We’ll put up a sign: ‘These are not our regular half-smokes.’ ”

Nizam isn’t exactly forthcoming when I ask him where the Chili Bowl gets its half-smokes. The sausage world by necessity is shrouded in secrecy. Packers are known to guard their recipes lest a competitor start churning out a nearly identical link and thereby poach distributors, and small grills like Ben’s sometimes rely on the uniqueness of their tube steaks.

“We don’t tell cooking shows, either,” Nizam says, somewhat apologetically. “Not to be overly secretive, but we’re famous, and we’re just one business in a changing community.”

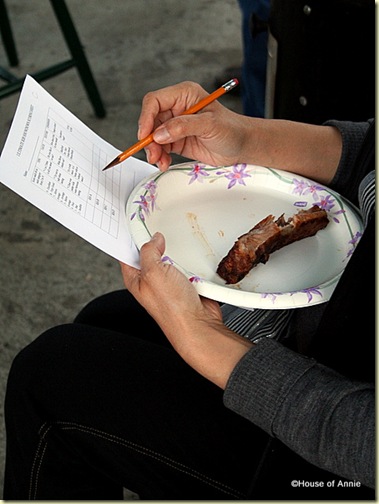

Since a good half-smoke is something you have to go searching for, I decide to get my hands on every sausage within the Beltway that meat distributors market as a half-smoke. It may not be the healthiest way to spend an afternoon, but I figure only a rigorous taste test of some half-dozen, locally store-bought links can determine which half-smoke is the half-smoke.

After retaining two City Paper co-workers to sample the various links with me, I reach out to Greggory Hill, chef and co-owner of the West End eatery David Greggory Restau Lounge, to function as both a grillman and judge. Hill seems like a logical choice; he’s not only a native Washingtonian who grew up eating half-smokes, he’s also a partner in M’Dawg Haute Dogs, a hot dog joint that will open soon in Adams Morgan’s nightlife district. Hill and his collaborators, Scott and Arianne Bennett, owners of the Amsterdam Falafelshop on the same boozy strip of 18th Street, will serve a dozen sausages that patrons will top themselves. At least one type of sausage has already been chosen.

“You’ve gotta have the half-smoke,” says Arianne Bennett.

When I approach Hill about a half-smoke bonanza, he explains that he and the Bennetts nearly killed themselves with sausage just days earlier. In their search for the right brands for their eatery, they had already sampled some 40 different dogs in an eat-a-thon, says Hill. Still, with hardly any coaxing, Hill agrees to a second round of battle—this one exclusively with the smokes.

I round up the hot and mild versions of five brands sold under the banner “half-smokes” at local stores: Kunzler, Gwaltney, Chesapeake Valley Farms, Briggs, and Manger’s. The first three hail from B.K. Miller Meats & Liquors in Clinton, Md., where half-smokes have been sold for much of the store’s 93-year history. (“There are definitely different levels of quality,” owner Blaise Miller III warns.) The latter two brands are purchased from Union Meats and Canales Quality Meats inside Eastern Market.

From the kitchen Hill first brings out a pair of metal trays filled with the grilled sausages from Gwaltney. Their skin provides a decent snap, but the innards seem especially homogenous. “Not that different from your average kielbasa,” one tester opines. The mild and spicy versions taste so marginally different that after a few samples we’re not sure which is which.

Next come the Chesapeake Valley Farms half-smokes. The bind in these is so loose that they break down when Hill tries to boil them dirty-water-style. One of them crumbles in his tongs. “This is really bad,” another co-worker groans. “Like liverwurst with heat put on it.” After just a few bites from the hot and mild we cast these mealy links to the side.

Hill then brings on the half-smokes from Kunzler. We find its consistency not much different from a supermarket hot dog, but the hot version is by far the spiciest yet. So far it’s Hill’s favorite. “It’s got texture, flavor, and spice,” he says. “When I want a half-smoke, I’m looking for a bit of heat.”

Considering their name, the Briggs half-smokes disappoint. They have a nice herbal flavor but not much kick. Worse yet, they have a gelatinous consistency that proves hard to work through with such a thick frank. I cast the carcass of mine onto the pile, as the diner bar is starting to look like the aftermath of a Coney Island wiener-eating competition. I can feel the panel losing steam.

Then Hill comes bearing a tray full of the final half-smokes, from Manger’s. The slices are visibly arresting; from feet away we spot globules of fat, and the mood brightens. “When I see this much fat on a sausage,” one taster explains, “it just makes me happy.” The skin snaps. The pork, beef, and grease balance nicely. And the spice builds as we work our way through the links.

“Now that’s a half-smoke,” says Hill. It has the closest resemblance to the sausage link of his youth. When I ask if he knows which half-smoke he’ll serve at the new eatery, he nods to the Manger’s. “Maybe now,” he says.

It may break a few hearts to hear that the best half-smoke at the bar in fact comes from Charm City. Seventy-one-year-old Alvin Manger, president of Manger Packing Corp., says the family company has been making sausages at the same location in West Baltimore since the 1880s. “We’re one of the last old German butchers in the area,” he says.

Manger Packing developed its half-smoke specifically for the District about 25 years ago, when it saw an opening in the market. Although Alvin Manger is predictably vague when discussing his half-smoke’s contents—“pork and beef…salt and spices,” he says—he does claim to supply half-smokes to the secretive folks over at Ben’s Chili Bowl. But he also says Ben’s sausage couldn’t be replicated by someone buying a standard Manger’s link from Eastern Market.

“We still keep Ben’s a little bit unique,” says Manger. “We made a deal with Ben’s and we keep our word.”

But such tinkering and customizing suggests there is no definitive half-smoke, just different versions. To see whether Manger’s half-smoke is unique, I overnight a box of them in dry ice to sausage expert and cookbook author Bruce Aidells, also known as the “King of Sausagedom,” in California. (True to his nickname, Aidells is actually in the midst of eating sausage when I first reach him by telephone.) After a close examination, he notes that the spicy half-smoke seems to be a close cousin of both the Texas hot link or smoky link (pork butt, garlic, cumin, red-pepper flakes), a popular item in the Lone Star State’s barbecue joints, and the Louisiana chaurice (pork butt, beef chuck, garlic, chili powder, cayenne), which is one of the spiciest sausages in that region’s cuisine.

“I do go out of my way to check out barbecue all over,” says Aidells, “and I’ve had similar sausage in barbecue joints around the country.”

Perhaps our signature sausage isn’t so unique after all. Gelatinous or course, spicy or mild, skin-on or skin-off, boiled or grilled—the half-smoke is whatever you want to think it is. That would be a disappointing discovery, if the half-smoke didn’t still have one inalienable trait—that you can only eat it right here.

Jan. 26, 2007 (Vol. 27, #4)

![[And the Winner Is: Miss Ann, right, of Ann's Snack Bar in Atlanta, above. Among the runners-up is Detroit's Miller's Bar, left.]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/pt-ae895A_burge_20070309164112.jpg)

![[Mr. Bartley's]](http://s.wsj.net/public/resources/images/PT-AE896C_burge_20070309154704.jpg)